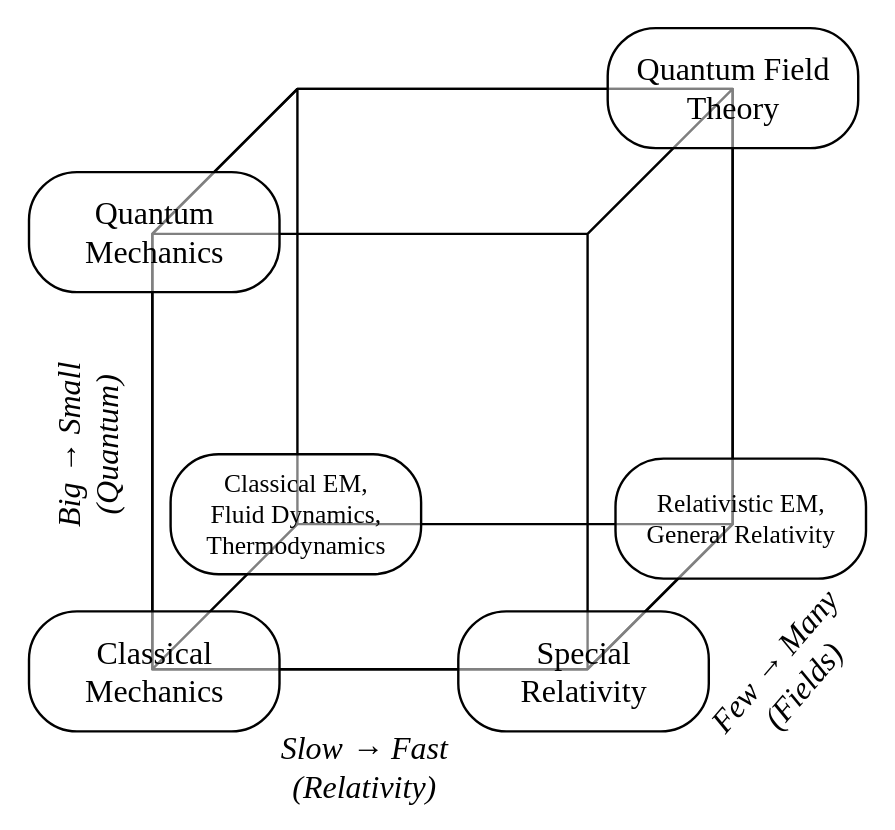

Revolutions in physics are forever memorialized by the dichotomies they introduce. While the hot new topics are given trendy labels of “quantum” or “relativistic” or whatnot, the old established players are relegated to the catch-all drawer of “classical stuff”. As with all human endeavors in categorizing things, these divisions should not be interpreted too rigidly. Some of the most interesting work in physics is done at their intersections. Conversely, these relatively modern divisions should not be regarded as the only useful ones. I want to bring up a less glamorized, yet no less important dichotomy which cuts across the more popular labels: the discrete versus the continuous.

To motivate this discussion, let’s talk about quantum field theory, or rather, the spooky allure it has to underinformed freshmen (like me). Before coming to college, I had only ever associated the mysterious “QFT” as some vague concept? possibly useful? in particle physics? It felt far removed from anything I had studied or was ever planning to learn — After all, high school didn’t exactly teach quantum mechanics, let alone field theories, or so I thought.

I did not know that linear algebra, for all its talk on eigenvalues and eigenvectors, forms the basis for quantization; Nor did I realize that electromagnetism, for all its talk of the electric and magnetic fields, is a classical field theory!

Over the years, I’ve come to realize that the barrier for me to learn new areas of physics is generally not my mathematical skills (a solid grasp of multivariable calculus and linear algebra is sufficient for most things) or conceptual understanding (science YouTubers and Wikipedia are more than enough for that), but the ability to somehow connect them together; to know how the things I’m learning now prepare me for the off-chance that I decide to study theoretical physics.

Which brings us back to my point about categories — they should never be treated as very sharp and hard-to-cross borders. (There’s an interesting parallel here to periodization in historiography that my amazing history professors are way more qualified to talk about.) And while part of this is just naivité, I think physics educators should also communicate the connections better.

One can add more transitional steps, like what Hyperphysics is doing:

But to better organize the bigger picture, I believe we just ought to come up with more dichotomies than the trendy nonrelativistic-relativistic and classical-quantum duals. It’s like how points on a page can be put closer together if we can crumble the paper into 3D: having more broad categories can reveal more connections.

So let’s talk about the discrete-versus-continuous dichotomy.

Introductory calculus-based physics courses always start off with Newtonian mechanics applied to particles — very few of them (i.e. discrete), generally less than three, because that’s when the equations begin to get messy and analytic solutions begin to fail. There may be some occasional forays into wave motion, but they generally stick to discrete systems all the way up to special relativity and Lagrangian mechanics, seldom considering throwing more particles into the pile.

On the other hand, introductory electromagnetism courses always introduce fields right away. However, they hesitate on electrodynamics and free-space wave propagation until multivariable calculus is satisfied. Lagrangian mechanics is generally not mentioned, nor changes in reference frames.

So the seeds of classical field theory are scattered between introductory physics courses, and sometimes omitted entirely. I don’t think this is necessarily a bad thing — solid foundations are incredibly important — but I believe for students interested in theoretical physics, the connections should be communicated better.

Demonstrating how wave motion arises from relatively small-scale perturbations applied to very large numbers of particles bridges this jump from discrete to continuous systems, and pointing out the classical quantization in the harmonics of standing waves bridges the jump from classical continuums to quantum.

The key realization for me is that these topics are not divided by their categories, but created by their actions: Quantum mechanics is quantized mechanics, field theories take the large-number limit of discrete systems, and so on. In that reference frame, the jumps don’t look that scary anymore.

(btw sorry I haven’t wrapped up the intergalactic medium post yet winter break is busyy)